Getting Acquired: Lessons Learned

On January 30th, 2015 the company that I co-founded, Aurelius, got acquired by DataStax. It was the first time that I negotiated and executed an acquisition of substantial size (>$1M) and this post summarizes the lessons I learned in the process [1].

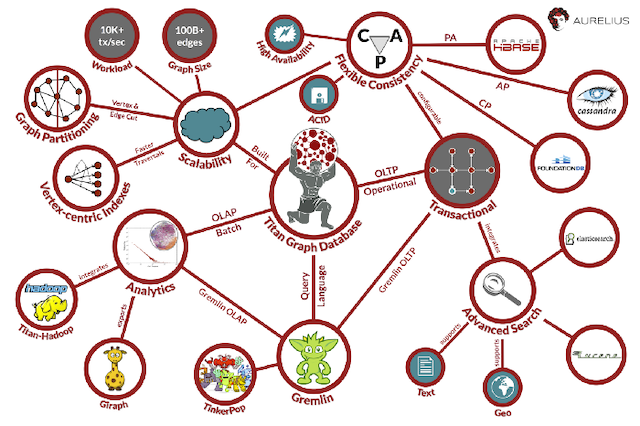

First, let me give you some context on the acquisition. Aurelius was a small company (10 employees) focused on graph database technology. We bootstrapped the company (i.e. no venture or angel funding) by providing consulting services for companies applying graph technology to their business problems. We build the TinkerPop graph stack as well as the distributed graph database Titan, both distributed under the Apache 2.0 software license. We had no marketing or sales staff and a single admin to keep things organized. Everybody else was a software engineer. Most of our engineering efforts were focused on advancing the above mentioned open source projects which acted as lead generators for our services offering. While being a services business on the surface, we saw this as a means to explore more scalable business models while staying cashflow positive [2]. An enterprise-ready (i.e. secure, supported, easy to use and operate, etc) version of Titan was repeatedly requested by our customers and since Titan builds on Cassandra it made sense to explore an acquisition by DataStax since DataStax had already laid the foundation for the associated business model and collected enough cash to execute it. DataStax is a privately held, venture-funded, late-stage startup with 400+ employees. I would classify the resulting acquisition as an “acquihire plus” because DataStax’ primary motivation for acquiring Aurelius was getting a functioning team of graph database experts and Aurelius’ assets (most of which were open source) were of secondary importance — however, our software assets and the “Titan” and “TinkerPop” brands and communities did play a role and hence it wasn’t a straight up acquihire. Without further ado, here are the lessons learned with a year-and-a-half worth of hindsight.

Getting to an acquisition is a long process

Finding the right acquirer is a lengthy and deliberate process. You don’t just call up a company and ask them if they want to acquire you much like you don’t walk up to a person and ask them to marry you. I mean, you can, but it’s a desperate move and called a “fire sale”. To not get into that position, you should scout potential acquirers well before you need to exit. An acquisition can be a great exit for your startup and even if you have no intention of selling, exploring your M&A exit options is never a bad idea as long as it doesn’t distract from your core responsibilities. Find out what adjacent technologies are used by your customers. Talk to company representatives at conferences, learn more about their business, attend their events, and establish healthy relationships with multiple people at a potential acquirer. You’ll get to know the company in a neutral context and see them as well as your relationships evolve over a period of time, which is incredibly important information to have when you consider an acquisition. If this sounds like dating advice, that’s no coincidence. There are lots of parallels. Getting introduced and doing a little bit of small talk, hanging out in the same circles, meeting up for beers, going on dates and, finally, sitting down to have “the talk”. The only difference is that there are more people involved on both sides which tends to make things a little more complicated.

It’s not just about the money

Of course money is an important part of it. You want the acquisition price to reflect the value of the business that you have created. However it shouldn’t be the only thing you optimize for. There are other important considerations like cultural fit, alignment of vision, future responsibilities and roles, as well as other aspects that matter to you and your team. You will likely stay with the acquirer for some time (at least the vesting period) and want to make sure this is time well spent. Make a ranked list of things that are important to you and your team aside from the price tag. This list will be very useful in the negotiation to avoid getting bogged down haggling over the price.

Stay involved in the legal process

An acquisition entails a ton of legal work: the initial offer, due diligence all sorts of disclosures intellectual property transfer Employment contract asset purchase agreement and many others. You will need a good legal team to guide you through this. However you should not outsource this completely or it can get really expensive. Lawyers will err on the side of caution and try to minimize your risk — that’s their job. But given the scope and complexity of an acquisition this can result in many billable hours and lawyers are not cheap. You need to guide your legal team to those areas that are important and tell them to ignore others. For instance, if you have a software business there are a lot of intellectual property questions the legal team will want to clarify. The acquirer likely wants to have guarantees that you did not steal somebody else’s code or infringed on their intellectual property [3]. Given the size of your code base and its associated dependency tree it is impossible to assess the associated risk comprehensively. This is where you need to make a judgement call on the likelihood of future litigation. I tried to stay involved in the legal process but — with hindsight — I could have saved ~$20K following this advice.

Continue Selling your Company

Obviously you have to make an effort to sell your company prior to an acquisition in order to demonstrate the value-add. It is less obvious that selling your company needs to continue after the acquisition has closed. The acquisition might have been a bet, or only a small number of people were involved in the acquisition negotiation. Whatever the reason, it is unlikely that everybody at the acquirer is entirely convinced of the value that you and your team will be adding to their company. The success of the acquisition partially depends on convincing those doubters and that’s largely your job in the coming months. It is in the interest of the acquirer to help you with that and you should reach out for support, but building a convincing narrative is up to you.

Find a Champion

Your team will be thrown into a new company culture and no matter the extent of “cultural fit” there will be stark differences. Managing the transition carefully and deliberately on both sides is an important part of a successful acquisition. Don’t expect that the pieces will just magically fall into place. There will be anxieties, expectations, and misunderstandings that need to be brought into the open and have to be addressed. Navigating this transitionary period is much easier if you can find a champion inside the acquiring company who will guide you. There are a gazillion things that are novel or subtly different in this new environment. A champion can point those out to you, shield you from some of them, and take a lot of burden off your shoulders. Note, that your champion should not be the person who led the acquisition. You want to find somebody who is closer to the trenches and an expert at navigating the day-to-day processes at the acquirer.

You are no longer the boss

You won’t be calling the shots anymore after you get acquired. That’s obvious but hard to adjust to. You’ve been used to making the decisions, determining the direction and getting things done quickly. Maybe you are leading a division inside the acquirer, but you no longer have these powers with respect to the entire company. You will depend on other departments and people that you don’t have control over. You have less (if any) influence over the company’s direction. You are starting from scratch in establishing your position in the informal trust network of the acquirer. Learn to manage your expectations and be prepared to hand over control. On the plus side, you are no longer responsible for everything, can hand things off to dedicated business functions, and focus on the work you enjoy doing.

Chill

An early stage startup is an intense experience. You are driving your business with a sense of urgency and adapt quickly to changing market forces in order to stay alive. Agility, speed of execution, focus and quickly learning from mistakes are important for early stage success. At larger companies the clocks run slower but they are also more robust to mistakes — they won’t fail because of a bad hire or a single bad product decision. That means your sense of urgency and intensity is not aligned with everybody else’s. You need to learn to chill in order to not drive the people around you insane. That’s easier said than done since those characteristics run to your core. I seriously annoyed some folks with my “we need to fix this immediately” activism and still cannot entirely contain myself. It’s good to point out potential areas for improvement but realize that change now takes time and be aware of the social dynamics. Go with the flow to be effective and less stressed out.

Summary

Getting acquired was not only a great exit but an exciting opportunity for personal growth. Becoming part of something larger and building a novel product together has been a great experience. It wasn’t always easy but never painful. A lot of credit for this is due to the wonderful people at DataStax who welcomed us warmly into their company. In particular, I would like to thank three individuals: Martin van Ryswyk (EVP of Engineering who led the acquisition), Sven Delmas (VP of Engineering and our champion), and Clint Smith (General Counsel who instilled sanity into the legal process). Last but not least, I want to thank the former Aurelius team for joining me on this journey and making it worthwhile. I hope that you find these notes helpful should you find yourself in a similar situation. Please use this thread for questions, comments or feedback.

Footnotes

[1]

Hopefully, entrepreneurs finding themselves in a similar situation will find this information useful. However, let me emphasize that I am not a lawyer and this is not sound legal advice. Please consult a lawyer that you trust to discuss your particular circumstances. I also strongly encourage you to ask other experienced entrepreneurs for their opinion which may differ from mine. For instance, you can read about the acquisition of Docstoc. Let me know of others to add here.

[2]

However, the cash flow produced by a highly differentiated, niche service offering with a continuous stream of inbound leads can be quite addictive. We charged between $250 and $500 an hour and had essentially no costs outside of HR. But we realized that this would be temporary until graph technology became established outside the big technology powerhouses.

[3]

For instance, maintain good hygiene around documenting contributions via CLAs for open source projects. Doing this after the fact is very laborious and stressful.

[4]

The opinions expressed in this post are my own and do not reflect those of my current or former employers.